Executive Summary

- In the past year at least 16 percent of Americans have traded cryptocurrencies – a $1.7 trillion industry that has grown significantly since 2017.

- Despite this market’s size and growth, cryptocurrencies fall into a number of regulatory gaps, and federal regulatory oversight of the market is severely underdeveloped.

- It is incumbent upon Congress to define the cryptocurrency industry and lay the appropriate regulatory groundwork before such decisions are made by existing regulators.

Introduction

A market that did not exist prior to 2017 is now causing headaches for regulators and policymakers in Washington as a growing number of Americans – an estimated 16 percent – invest in, trade, or use cryptocurrencies. Wyoming and Arizona are reportedly considering accepting tax payments in the form of digital currencies. New York’s new mayor took his first paycheck in cryptocurrencies.

While (or perhaps because) the broad, long-term economic implications of cryptocurrencies remain unknown, the market value of cryptocurrencies exceeded $3 trillion in November of last year. Any market or industry of this size deserves rigorous scrutiny by policymakers and regulators, forward-looking analysis, and examination—and this is particularly true for a market in which individual Americans have little in the way of consumer protections. To date, Congress has not yet performed this review and analysis, but this may finally be changing. This week will see Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) Chair Rostin Behnam testify before Congress at a hearing examining the risks, regulation, and innovation of digital assets.

Below are five fundamental questions that Congress must seek to answer in considering how to appropriately regulate the cryptocurrency market. If Congress does not take ownership of this nascent industry, cryptocurrency issuers and users will likely face a patchwork of conflicting agency-led initiatives, or worse, no regulatory oversight at all.

What Is a Cryptocurrency?

A cryptocurrency is a digital or virtual currency, underpinned by advanced encryption algorithms that allow cryptocurrency users to obtain cryptocurrencies without the use of third-party intermediaries – it is decentralized, and not usually managed by a central authority. The encryption algorithms and advanced cryptographic processes are held on blockchain, an open distributed ledger that creates a unified transaction record, promising real-time transparency to all users.

The most important problem facing Congress and regulators is that it can be difficult to know what a cryptocurrency is for. While the primary purpose of a currency is to exchange it for goods and services, most users of cryptocurrencies are instead investing in or trading cryptocurrencies. Although the United States has over 30,000 bitcoin ATMs, it remains difficult to actually use Bitcoin to pay for goods or services.

This raises the question of how to best define cryptocurrencies for the purpose of regulation. Cryptocurrencies, as digital currencies, are unquestionably an asset, but what kind of asset? If the primary purpose of a cryptocurrency is to be used to pay for goods and services, it would be appropriate to classify it as a commodity, like a metal. If instead a cryptocurrency is primarily a financially tradeable instrument, it would be appropriate to classify it as a security. Bitcoin, the world’s first cryptocurrency, is regulated as a commodity, but the Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) has said that in its view most cryptocurrencies are securities. This distinction matters, because securities are regulated significantly more stringently than commodities, including, among other requirements, restrictions on price fixing.

Given the questions as to both the current role, and future evolution, of cryptocurrencies, regulating this class of assets is something of a moving target.

How Should We Think About Regulating Cryptocurrency Issuers?

Most cryptocurrencies are currently issued by a relatively new class of financial vehicle, the fintech – so called because they share the properties of both financial services firms and technology firms. Fintechs are typically fast, nimble startups seeking to challenge entrenched financial services providers by providing traditional services better, reaching underserved markets, or offering brand-new combinations of products and product offerings. Where this becomes challenging for regulators is where fintechs provide banking and banking-like services. By issuing cryptocurrencies and seeking to challenge the supremacy of established banks, most fintechs have morphed from back-office service providers to increasingly providing customer-focused finance options. In short, many of these quasi-banks provide quasi-bank like services, without the exhaustive bank supervision and oversight regulatory system.

While relief from a burdensome regulatory regime can be a good thing, particularly for a new industry, there is significant scope for customer abuses and, at the extreme end of the scale, the potential for consequences to the economy broadly. One of the defining characteristics of a bank is that it is required to purchase insurance from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), which offers consumers and investors a degree of comfort if the bank enters material financial distress. This same protection is not provided to fintechs, although the scale of the vast majority of fintechs is not material to the economy – yet.

Who Should Regulate Cryptocurrencies and Cryptocurrency Issuers?

The federal government’s reticence to identify precisely what a cryptocurrency is makes it difficult to determine which federal agency ought to be responsible. No administration nor any Congress has yet taken a stand. The necessary result has been that what regulatory oversight exists has been a turf war between the financial regulators. This is not to imply that the decision is an easy one: The currency aspects of cryptocurrency concern the Federal Reserve and Treasury; the commodity aspects the CFTC; and the securities aspects the SEC. The responsible regulator may even differ depending on the cryptocurrency issuer, with parties ranging from the Fed, to the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, to even the Small Business Administration. The FDIC is waiting in the wings if any of these fintechs require bank charters (usually to deny them). Even outside of the federal financial services regulators, there are broader privacy and security issues that might concern the National Economic Council or the Financial Stability Oversight Council.

The tenor, burden, and characteristics of the regulatory response will differ wildly depending on the responsible federal agency (or worse, multiple agencies). Whichever federal agency or agencies is ultimately made responsible will then face a number of operational challenges, as this new brief will require staff, time, and expertise to address, even as the new ordinary course of business, let alone the time it will take to meet the needs of regulating cryptocurrencies. The relevant body may even need to consider its charter as to its applicability given these expanded responsibilities.

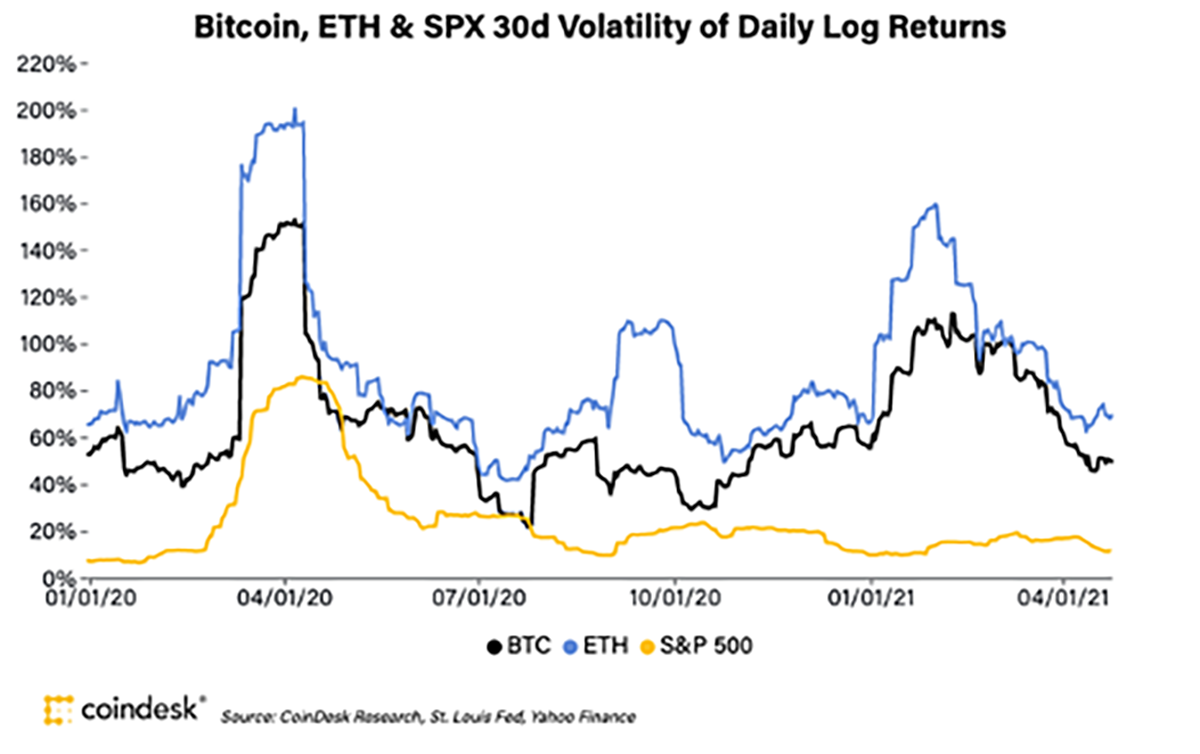

Even if the correct agency can be identified and has an abundance of regulatory resources, it also remains true that cryptocurrency is inherently quite a tricky beast in and of itself to regulate. One of the key reasons for this is cryptocurrency’s high volatility (technically a measure of dispersion around the mean value of a security, but more generally rapid or significant fluctuations in value as defined by the market). The graphic below shows the daily log return (a calculation of return on equity) of the first and second most significant cryptocurrencies, bitcoin and Ethereum, by comparison to the average volatility of the S&P 500.

Any asset class that behaves unpredictably – and so unpredictably – will be a challenge for any regulator.

Should the U.S. Government Back a Cryptocurrency?

All these concerns have so far been pointed at cryptocurrency as represented by private industry. Congress might also consider, further down the line, the idea of a federally backed cryptocurrency, or central bank digital currency (CBDC). Proponents of cryptocurrencies point to the speed and transparency offered to consumers by crypto and in some cases forecast not just that the traditional banking sector is in danger, but also eventually the U.S. dollar.

Since the 1944 Bretton Woods agreement, world currencies have been pegged not to gold but to the U.S. dollar, under the reasoning that it itself was pegged to gold. Despite President Nixon’s decoupling of the dollar and gold and the subsequent emergence of the system of fiat money currencies in global use today, the U.S. dollar remains the global reserve currency, and that is unlikely to change given the stability and liquidity of U.S. Treasuries supporting the dollar as the world’s most redeemable currency.

This situation could of course change if a sufficiently strong digital contender emerges, with the most obvious contender a CBDC backed by the Chinese government. Although this risk may still be decades off, one of the most effective ways to forestall it would be the creation of a U.S. CBDC. A recent Fed discussion paper considers the potential benefits and risks of a CBDC and represents the first step taken by the U.S. government in this direction.

What Is the Right Balance of Regulation?

Even if the federal government can address these preliminary, theoretical questions to determine how it should regulate cryptocurrencies, the government will also have to strike the correct balance as to how much. Push the balance too far in one direction, and the federal government will overly burden cryptocurrency issuers, discourage innovation, and harm U.S. global market competitiveness. Too far in the other direction, and the federal government may fail to adequately protect both consumers and investors.

Conclusions

Whether cryptocurrencies will have the staying power to make a significant long-term impact on U.S. or global economies is unclear. Even accounting for the volatility of cryptocurrencies, however, the cryptocurrency market is lurching from strength (to weakness) to strength. Congress has an opportunity to set broad industry guardrails, protect consumers and investors, and create a unified vision for the new market that best employs regulatory resources and fosters innovation in U.S. financial markets. That opportunity is swiftly disappearing.

(function(d, s, id) {

var js, fjs = d.getElementsByTagName(s)[0];

if (d.getElementById(id)) return;

js = d.createElement(s); js.id = id;

js.src = “//connect.facebook.net/en_US/all.js#xfbml=1”;

fjs.parentNode.insertBefore(js, fjs);

}(document, ‘script’, ‘facebook-jssdk’));

Source link