Russia’s economy is too large to be kept afloat on crypto, analysts say.

Artur Widak/NurPhoto via Getty Images

The US and its allies continue to expand sanctions against Russia in response to its ongoing invasion of Ukraine — blocking state-owned companies and central banks abroad, limiting exports of vital technology and freezing the assets of President Vladimir Putin’s allies.

“These individuals have enriched themselves at the expense of the Russian people, and some have elevated their family members into high-ranking positions,” read a White House release last week that singled out telecom magnate Alisher Usmanov, worth a reported $14.5 billion, and several other Russian elites. “Others sit atop Russia’s largest companies and are responsible for providing the resources necessary to support Putin’s invasion of Ukraine.”

But questions have arisen about whether the government in Moscow, Russia’s state-owned corporations and wealthy oligarchs can sidestep the financial squeeze of sanctions with cryptocurrencies, which operate on decentralized networks that ignore international borders.

Here’s what you need to know about whether Russia can capitalize on cryptocurrency to circumvent economic sanctions.

What is cryptocurrency?

Unlike traditional money, which requires a government or bank to maintain its value, cryptocurrency is a decentralized digital payment system that can be sent by anyone to anyone in the world.

The process is encrypted, theoretically making it both safer and harder to track than traditional financial transactions.

As with stocks, the value of cryptocurrency is ultimately determined by what people are willing to pay for it — though crypto is much more volatile.

Cryptocurrency is a decentralized digital payment system that can be sent by anyone to anyone in the world.

Boris Zhitkov

Why Russia would turn to cryptocurrency

In theory, cryptocurrency allows you to sidestep banks and governmental regulators with direct peer-to-peer transfers. That could be useful if you’re frozen out of traditional financial institutions

There is precedent: In May 2021, blockchain analytics company Elliptic reported that Iran was bitcoin-mining to generate hundreds of millions of dollars. “Bitcoin-mining represents an attractive opportunity for a sanctions-hit economy suffering from a shortage of hard cash, but with a surplus of oil and natural gas,” the firm wrote in a blog post.

And a United Nations report from February indicated that North Korea used as much as $400 million in stolen ether, bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies to finance its nuclear and ballistic missile programs, in defiance of UN sanctions.

Too big for bitcoin

But that’s not likely to work in the current situation, says Ari Redbord, head of legal and government affairs at blockchain intelligence firm TRM Labs.

“Iran and North Korea don’t approach the size of the Russian economy,” Redbord told CNET. “While they may have been able to launder hundreds of millions in cryptocurrency, that doesn’t come close to what it would take for Russia — a G20 economy — to evade sanctions in a meaningful way.”

Unlike North Korea and Iran, Russia has been enmeshed in global financial markets for decades. Under normal circumstances, 80% of its daily foreign exchange transactions and half of its international trade is conducted in US dollars, according to Al Jazeera.

The Russian government had been building up reserves of dollars and other currencies, but not crypto, according to Todd Conklin of the US Treasury Department’s Office of Terrorism and Financial Intelligence.

“In fact, they’ve shown signs of being reticent to move in that direction over the last two years, while they’ve built up their own internal reserves,” Conklin told TRM. “You can’t flip a switch overnight and run a G20 economy on cryptocurrency.”

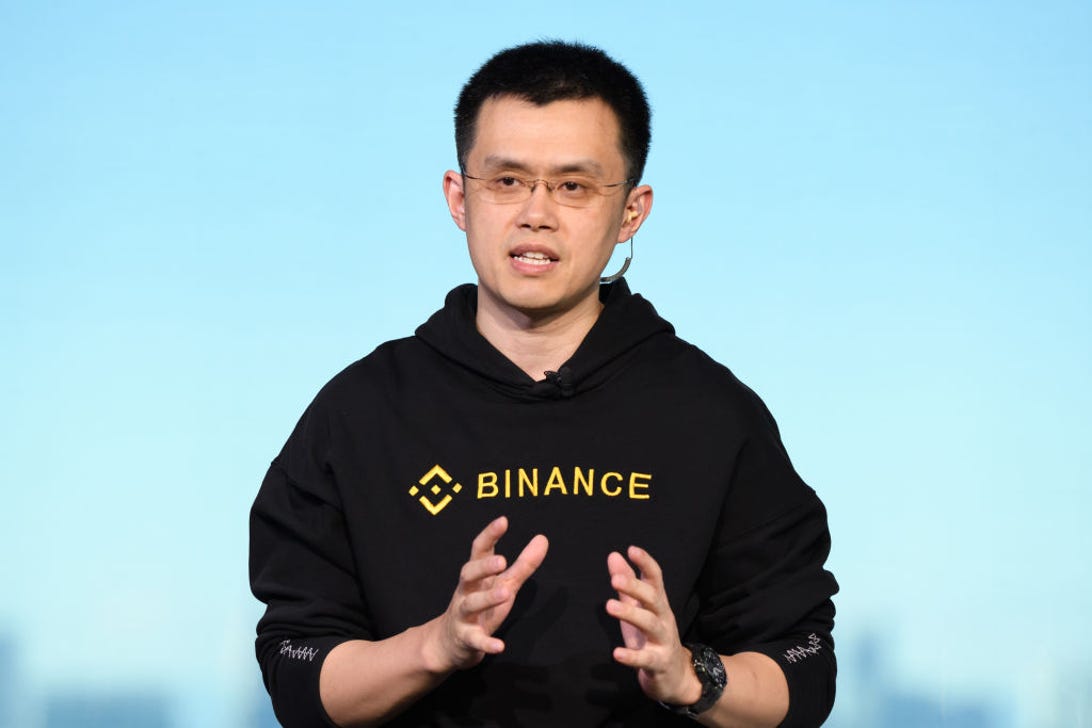

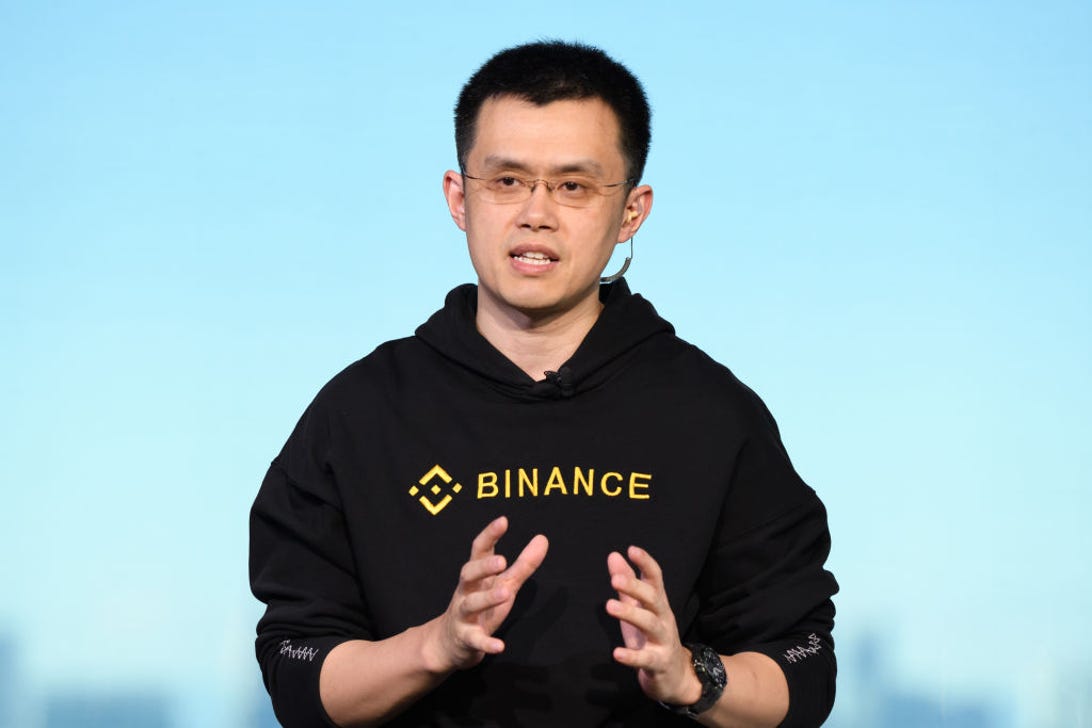

“Crypto is too small for Russia,” Binance CEO Changpeng Zhao said.

Akio Kon/Bloomberg/Getty Images

The entire cryptocurrency market — now valued at approximately $1.7 trillion — doesn’t compare to the amount being frozen by the West.

“Then you add trade deficits and funding an increasingly expensive war, and it’s just not workable,” Redbord said. “When you’re talking about large-scale sanctions against entire sectors, crypto doesn’t allow that kind of scale.”

Changpeng Zhao, CEO of Binance, the world’s largest cryptocurrency exchange, agrees that “crypto is too small for Russia.”

He posited in a March 4 blog post that less than 0.3% of the global net worth is invested in digital currency — hardly enough to replace a G20 economy like Russia.

It’s also too traceable.

“You simply cannot move millions of dollars into crypto without people noticing,” Zhao said. “The traditional financial system is far more susceptible to money laundering and sanctions-busting than crypto will ever be.”

The large markets that do have the liquidity to move massive amounts of crypto have robust compliance controls, especially in the US. “There’s a perception crypto is the Wild West, but in the case of money laundering, it’s regulated like any other industry,” Redbord said.

Because blockchain operates with an open ledger, it’s easy to trace the flow of cryptocurrency, he added, using tools like the ones created by TRM, which often works closely with law enforcement.

“You can move crypto around, but you need to find ‘off-ramps’ to spend it in the real world,” he added. “And that’s really hard. People aren’t buying bread or weapons with cryptocurrency.”

The cautionary tale of Bitfinex

Crypto advocates point to the saga of Bitfinex, an exchange registered in the British Virgin Islands, as proof of how hard it is to get away with using blockchain technology for money laundering. In 2016, Bitfinex announced that it had been hacked and that about $72 million in bitcoin had been stolen.

In February of this year, husband and wife Ilya Lichtenstein and Heather Morgan were arrested in conjunction with the breach and charged with conspiracy to launder money and to defraud the US.

Rafael Henrique/SOPA Images/LightRocket/Getty Images

By that time, the cryptocurrency had been laundered across blockchains and increased in value to $3.6 billion, making it the largest financial seizure ever.

“Looking at the Bitfinex hack, you can, in theory, steal $3.6 billion worth of bitcoin, but you can’t use them without getting caught,” said Redbord. “You can do things to mask your transactions, like chain-hopping,” or jumping from one cryptocurrency to another in rapid succession. “But regulators can ultimately follow the flow of bitcoin across chains.”

Slipping through the cracks

While the Russian government and major companies are too large to nimbly use cryptocurrency to continue making international payments in regions where they’ve been frozen out, it could be a more attractive approach for individuals, who operate on a much smaller scale.

Cryptocurrency “might be one aspect of their sanction evasion playbook,” Redbord, a former federal prosecutor, said. “They’ll also use shell companies, high-end art, real estate, expensive cars.”

But legitimate crypto exchanges are on the lookout. Coinbase, a US platform that generated $1.14 billion in revenue in 2020, has blocked some 25,000 accounts “related to Russian individuals or entities we believe to be engaging in illicit activity.”

They’d have to use exchanges that don’t comply with the Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control, many of which are based in Russia and “will be targets for authorities,” Redbord said.

In September, OFAC targeted digital currency exchanges for the first time when it sanctioned Suex, a crypto transferring service with Russian ties, for facilitating ransomware payments.

According to the Treasury Department, 40% of Suex’s known transaction history “is associated with illicit actors.”

“The Treasury Department has become more sophisticated about digital banking,” Redbord said. “They’ve rung the alarm about these noncompliant exchanges. No one who is concerned about secondary sanctions is doing business with them.”

Even if you operate with noncompliant exchanges, he said, as soon as you interact with a regulated one, the whole house of cards collapses.